In a world where we're quick to dub every raindrop a "thundersnow bomb," it's time we hearken back to the days when a devastating storm was just that—a storm. The Great Storm of 1703, with its immense power and the resilience of those who lived through it, poses an intriguing contrast to today's penchant for weather forecast hyperbole. Are we amplifying minor inconveniences into major crises, or have we genuinely evolved to be more cautious? More on this below. Keep reading, and remember, sometimes, a storm is just a storm.

In November 1703, England bore witness to one of its most cataclysmic natural calamities. The storm, infamous for its ferocity, wrought havoc across the nation, claiming approximately 30,000 lives, both at sea and on land. Ancient trees were mercilessly uprooted, and the tempestuous winds ripped roofs from buildings. In this article, we will delve into the historical narrative of the Great Storm of 1703, exploring its impact and contrasting it with modern-day weather phenomena.

The Wrath of Nature

The year 1703 was a time when electricity remained undiscovered, and the concept of global warming had yet to be conceived. Consequently, the hurricane-strength storm that raged for an entire week was perceived as an act of God's wrath, as noted by renowned author, broadcaster, and opinion columnist Richard Littlejohn in his article for the Daily Mail. He poignantly quipped, "Nobody thought to give it a name, and there was no Met Office to issue an amber alert and blame it all on alleged man-made climate change."

A Different Era of Weather Events

In the centuries that followed the Great Storm of 1703, the British Isles experienced various severe weather events, none of which were met with the same level of alarm that characterizes contemporary reactions to even minor weather disturbances. One notable event was the 1987 hurricane, forever etched in memory alongside BBC's weatherman Michael Fish. While it did cause significant damage, life swiftly returned to normalcy the next day. The response was decidedly more measured compared to the modern era of sensationalized weather forecasts.

Storm Ciaran: A Case Study in Hype

The article goes on to discuss the recent Storm Ciaran and its consequences. While acknowledging the genuine suffering experienced by individuals whose homes and businesses were inundated, it scrutinizes the excessive reaction that accompanied the storm. Comparing the situation to major natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina, it becomes evident that the sensationalism surrounding such events has grown in recent times.

The Rise of Hyperbolic Reporting

The evolution of hyperbolic reporting is a notable trend. Weather forecasters, once grounded in measured predictions, now exude the drama of Hollywood disaster movies. Reporters in the field are eager to portray themselves in the most dramatic light, perhaps even resorting to staged theatrics. This hyperbole is further exacerbated by the adoption of American conventions, including the naming of storms, akin to Hollywood blockbuster titles.

Reflecting on the Past

The article reminisces about the era when 24-hour television and social media had not yet transformed the nation's outlook. Back then, the indomitable spirit of "Keep Calm And Carry On" from wartime Britain prevailed. Present-day reactions to inconvenience, it seems, are marked by panic rather than resilience.

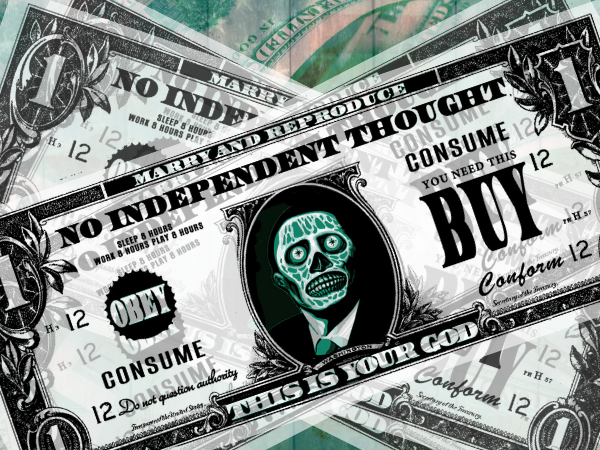

A Culture of Fear

Official predictions of impending catastrophes contribute to a culture of fear, which can lead to irrational behaviors such as stockpiling essential supplies. The Met Office, once regarded for its measured assessments and predictions, now often resorts to fear-inducing language, characterizing weather phenomena as "weather bombs" and even coining dramatic terms like "thundersnow."

The Future of Weather Reporting

In a world where even a downpour is described as a "bomb," the article questions how future media will handle real crises and disasters. It humorously envisions millennials grappling with life without electricity or a reliable 5G signal. The 1703 storm, if it occurred today, would likely perplex a generation accustomed to constant connectivity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Great Storm of 1703 serves as a reminder of England's historical resilience in the face of natural disasters. Contrasting it with contemporary weather events highlights the transformation of weather reporting into a sensationalized spectacle. While public safety and awareness are undoubtedly important, it is essential to strike a balance between conveying the gravity of situations and preventing unnecessary panic. Perhaps, as the article suggests, we need to return to a more measured and stoic approach, similar to the spirit of generations past.

Hot Take: Hyperbolic weather reporting might just be the true "thunderstorm" in our lives, obscuring the real issues with a deluge of sensationalism.

Support My Journey

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please consider donating! I’m saving up to buy a used car to keep my travels (and stories) rolling. Every little bit helps — and is deeply appreciated. GoGetFunding